In the frigid, dark depths of the Pacific Ocean, the seafloor is strewn with metallic stones that mining companies desire greatly—alongside vast populations of bizarre and uncommon creatures that remain largely unfamiliar to scientific community.

Scientists are hurriedly working to classify numerous recently found species with names.

The mining sector is urging regulatory bodies to finalize guidelines that might pave the way for extracting resources from portions of the extensive Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) located between Hawaii and Mexico.

Previously considered an undersea desert, the CCZ is now recognized for its rich biodiversity.

They vary from minuscule worms dwelling in the murky sediments to buoyant sponges anchored to the rocks akin to water-filled balloons, and a colossal sea cucumber nicknamed the "gummy squirrel."

Activists argue that this variety of life forms represents the genuine wealth of our planet's biggest and most mysterious ecosystem.

Experts caution that mining activities might push species toward extinction before we can even identify them.

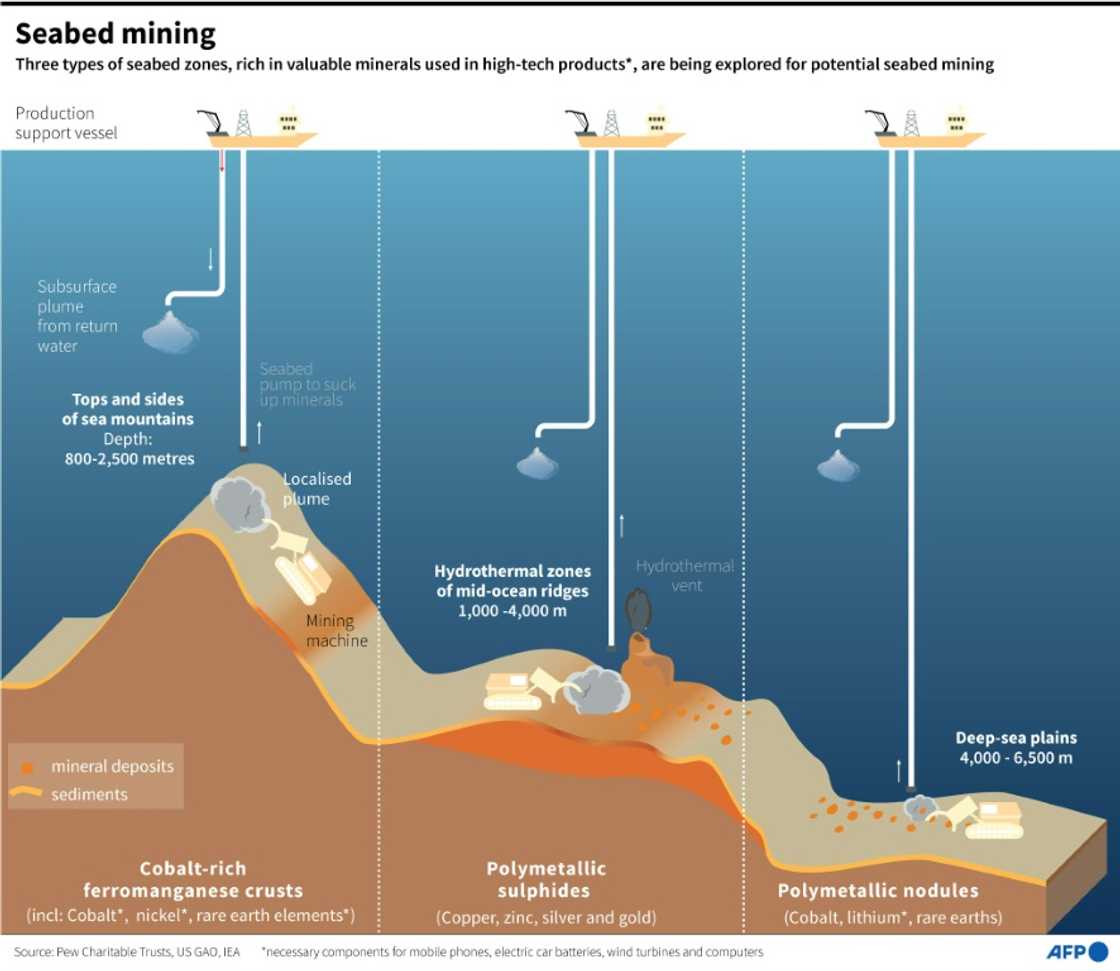

The interest in extracting the "nodules," which are roughly the size of potatoes and hold metals utilized in technologies like smartphone touchscreens and rechargeable batteries, has led researchers to investigate the CCZ area.

"As a result of our efforts to exploit that region, we now possess a much deeper comprehension of it than we otherwise would have attained," stated Tammy Horton from Britain’s National Oceanography Centre (NOC).

Researchers have retrieved sediments using box cores launched from vessels and utilized remotely operated vehicles to capture images and gather specimens from the ocean floor.

In any specific area of the CCZ seabed, a quick look might reveal only one lone brittle star, yet scientists rarely encounter the same individual more than once.

Horton mentioned that there are "substantial populations of uncommon species," noting that much of this biodiversity is found within organisms residing in the sediment.

The nodules also create their own distinct habitats, much like tiny coral gardens.

'First step'

The initial inventory of data from scientific investigations in the CCZ, released in 2023, revealed that approximately 90 percent of the 5,000 animal species documented were previously unknown to scientists.

The ISA aims to have more than a thousand species documented by 2030 in areas of interest to mining companies.

The process is painstaking.

Whenever feasible, every creature should be illustrated, dissected, and given a molecular "barcode," which serves as a type of DNA fingerprint enabling other scientists to recognize it.

Horton and her team of experts spent an entire year describing 27 out of over a hundred unnamed amphipods — a species of small crustaceans.

"The primary and essential initial step towards comprehending any environment involves identifying the species present, determining their population sizes, and mapping out the extent of their habitat," she explained to AFP.

This would outline a foundation for understanding life in the abyssal plains, enabling a clearer comprehension of possible adverse impacts.

The conservation organization Fauna & Flora has stated that the risks include harm to the marine food chain as well as the possibility of intensifying climate change due to the disturbance of sediments that store heat-trapping carbon.

The ISA has to finalize the global deep-sea mining regulations this year, however, significant tasks remain unfinished.

Cold War connections

The most ancient mining trial area encompasses a segment of the CCZ seafloor that was cultivated in 1979.

Daniel Jones, a NOC researcher who sifted through archival records to determine the precise location, revealed that the operation was part of a CIA scheme aimed at retrieving a Russian nuclear submarine by disguising their efforts as deep-sea mining activities.

According to Jones, the CIA rented a vessel for actual deep-sea mining operations.

He discovered an ancient photo depicting the approximately eight-meter-(26-foot)-wide device utilized for collecting nodules.

His group went to the testing location in 2023, over four decades following the initial disruption.

He mentioned that the machine trails could still be easily seen on the ocean floor.

Jones informed journalists lately that they observed "initial signs of biological restoration" on the mining-affected paths; however, animal populations had yet to return to their usual levels.

The sluggish rate at which changes occur in the CCZ can be seen through the nodules, which have probably taken millions of years to form.

Each likely began as a fragment of solid material — such as a shark’s tooth or a fish’s otolith — that came to rest on the ocean floor.

They gradually expanded next, as they attracted minerals present in the water at very low concentrations.

They include metals such as cobalt that are highly sought after during the energy shift.

However, the European Academies of Science Advisory Council (EASAC) has stated that the requirement for the nodules has been exaggerated and has called for a halt to mining activities.

Michael Norton, the EASAC Environment Director, stated that initiating deep-sea exploitation would likely prove difficult to halt thereafter.

It’s a one-way road," he stated. "Once you head down it, you won’t turn back easily.