In 1978, Terrence Malick was regarded as one of the most promising newcomers in Hollywood. His sophomore movie Days of Heaven was a pure triumph following his exceptional 1973 first album Badlands . Malick had endless possibilities for his next project. However, according to the Hollywood legend, he vanished from public view instead.

Malick astonishingly returned to the big screen after two decades with his third movie. The Thin Red Line Today, this mysterious director has become highly productive. From 2011 to 2019, they unveiled six movies. This marks quite a shift from the long gap between their second and third features.

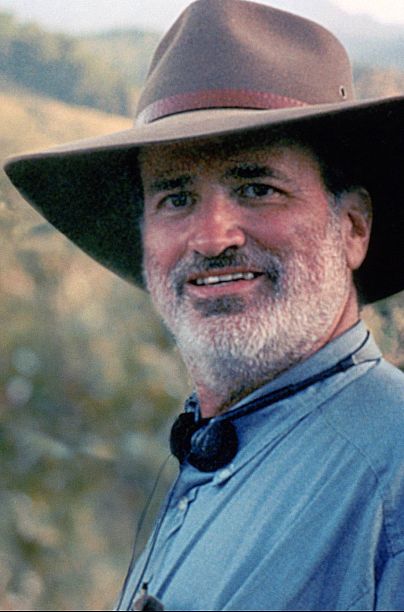

Despite the higher productivity, Malick remains an enigma. His last known interview was with the French newspaper Le Monde back in 1979. Since then, he hasn’t granted any interviews to journalists, and the sole photograph he has permitted for public release is a blurry promo image of himself at work directing. The Thin Red Line .

The scene is invariably illuminated with the warm glow of late afternoon—the so-called 'magic hour.' This photograph was captured by his father, Emil Malick. Despite their disagreements, Terry continued to view himself through his dad's perspective," states the biography accompanying the image. Appearing midway through the book, this passage encapsulates much of John Bleasdale’s significant challenge: offering an understanding of both Malick’s human side and his distinctive style within the realm of cinema.

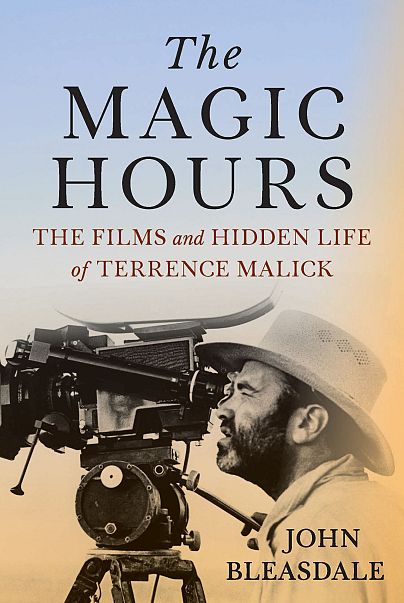

"The Magic Hours: The Films and Hidden Life of Terrence Malick" offers an extensive look at the renowned filmmaker's life, showcasing thorough research through detailed exploration of the challenges involved in leading large teams both in front of and behind the camera. Bleasdale enriches this work with excerpts from newspapers, insights from colleagues, and his personal reflections on Malick’s body of work.

This marks the first time Malick has been the subject of a biography. As expected, there is curiosity about whether Bleasdale managed to secure an interview with Malick directly. Although he mentions discussions with longtime associates including production designer Jack Fisk and actors like Sean Penn, he dismisses the idea of having spent significant time with Malick by saying they only exchanged "very courteous email correspondence."

However, "The Magic Hours" explores more aspects of Malick’s private life than any previous individual source. Whether any of these details come directly from him, despite not being explicitly attributed to him, remains unclear. The most definitive response I receive from Bleasdale is: “If there were, I wouldn’t be able to reveal it.”

While the detailed biography of Malick's career is fascinating—especially the part about his difficult period known as the "wilderness years" and how his challenging times with producers Bobby Geisler and John Roberdeau fueled his creative inspiration—it remains intriguing. Knight of Cups - The most compelling parts of the book delve into how Malick’s personal life overlapped with his professional journey.

Bleasdale’s biography portrays Malick as an affable and highly likable individual, equally inclined towards lighthearted banter and profound contemplation. Despite acknowledging his introverted nature, the book makes it evident that one should not accept at face value the myths about him being a recluse in Hollywood.

As these legends are dispelled, details regarding Malick’s domestic life come to light. His strained connection with his father, the absence of his siblings, and his romantic entanglements all contribute to Bleasdale’s interpretations of his movies and how they correlate with their respective release periods.

"He observes that tragic brothers and troubled fathers recur throughout his films." However, even though aspects of his marriage to Michèle Monette shed some light on these themes, they do not fully reveal everything. To The Wonder Bleasdale makes it evident that his body of work is not merely concealed autobiography.

I believe he strongly wishes to conceal aspects of his personal life," Bleasdale states. Similar to how his philosophical background and religious convictions frequently act as starting points for comprehending Terrence Malick’s body of work, Bleasdale argues this approach overlooks the essence. "He likely believes that if people view these elements as the ultimate keys to understanding all his films, it might hinder their ability to engage with the movies personally and extract meanings independently.

If Malick deliberately avoids public attention in an effort akin to Barthes' 'Death of the Author,' aiming to prevent his personal life from overshadowing audience interpretation of his work, wouldn't a biography contradict his creative intentions? Bleasdale suggests this might be a misinterpretation of Malick’s distancing from media exposure.

Bleasdale states, "He will never pick up this book." He once mentioned that he wouldn’t attend therapy as it would drain his energy. Instead of opening up during interviews, he prefers to explore his inner self through his films.

Similar to his AFI classmate David Lynch’s well-known reluctance to explain the meanings behind his movies, Malick’s primary focus regarding his public persona is solely on his films themselves.

Interacting with these films, be it through subsequent discussions or even biographies, allows them to become part of our world. "Ideally, the purpose of any film-related book should be to encourage readers to revisit the movies and appreciate them in greater depth," explains Bleasdale.

"The Magic Hours" fulfills this commitment. It immerses itself completely in how Malick integrates his personal story into a filmmaking approach that elevates the artistry. The fact that it achieves this with Malick’s most controversial films is even more noteworthy compared to what he does with those beloved by fans. As Bleasdale outlines in his section on this topic, To The Wonder There is much more to his approach to filmmaking than just the apparent link between the story and his second wife.

"It’s strange. The film is ostensibly autobiographical, yet it’s entirely narrated through Marina’s [Olga Kurylenko]'s perspective. Ben Affleck barely has three lines throughout the entire movie. It primarily focuses on her character along with Javier Bardem playing a roving priest." Bleasdale suggests that even when Malick delves into autobiography, he remains creatively innovative. "An autobiography doesn’t always mean laying bare one's personal reflections; instead, it can involve examining various viewpoints from past experiences. This approach is quite magnanimous," she explains.

If Malick’s initial trio of films were regarded as masterpieces and his fifth – which was equally autobiographical – The Tree of Life solidified his comeback with the Palme d'Or at Cannes and Academy Award nominations; however, his subsequent movies have mostly faced criticism for being tedious and aimlessly spiritual, often resembling scenes from a perfume commercial.

Bleasdale contends that despite being highly abstract, his work still embodies an avant-garde artistic approach which continues to have a significant impact on cinema, much like his previous works.

Out of Malick's seven films produced in the 21st century, five were shot by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (nicknamed Chivo). Their collaboration has established a distinctive visual style that characterizes their work together.

Over Chivo's debut collaboration with Malick on his first film, The New World , they developed a "dogma" for filming that involved using "only available natural light; underexposure was strictly prohibited," along with other guidelines that discourage zooming and prefer movements "along the z-axis" over pans and tilts. This set of rules has become characteristic of Malick's films—sometimes even parodied—but has also influenced modern cinema. Chivo received his third Oscar for this work on The Revenant , a movie featuring distinct bear claw marks inspired by Malick’s work.

Bleasdale mentions films and directors that clearly show the impact of Malick’s work. He points out Paul Thomas Anderson’s movies as examples. There Will Be Blood and The Master owe a significant debt to Malick’s period pieces. From last year’s Oppenheimer “You won’t find that type of editing with two scenes split throughout the entire film; instead, most of the storytelling consists of individual shots rather than complete scenes, excluding 'The Tree of Life.'” Even this year’s contender for Best Picture was different. Nickel Boys is “totally The Tree of Life in its technique of montage and use of subjective camera work.

If his work doesn’t appeal to a general audience, it’s because he’s pushing boundaries by experimenting with cinematic storytelling techniques, according to Bleasdale. The aim is always to narrate tales that resonate with audiences through innovative approaches.

As someone not previously swayed by Terrence Malick’s work, Bleasdale presents compelling arguments for appreciating Malick both as a director and an individual through “The Magic Hours.” This portrayal becomes particularly captivating when stripped of the enigmatic veil often perpetuated by media coverage.

As he cites one of Malick’s colleagues: "We truly thought each day at work that our aim was to revolutionize the cinematic language."

"The Magic Hours: The Films and Secret Life of Terrence Malick," authored by John Bleasdale, is currently available.