The process of clearing out one's living space from hametz (Leaven) removal before Passover stems from a Torah commandment. This practice is detailed in Exodus where it states, "For seven days you must eat matzah, yet on the day prior to the festival, ensure all se'or is removed from your home; for whoever consumes leaven, that individual shall be excommunicated..." (12:15).

The initial Mishnah of Tractate "Pesach" (Passover) begins with this instruction: "On the eve of the 14th day of Nisan, we conduct a search for chametz using the illumination from a lamp."

Even though both sources do not highlight it as a familial event, bedikat hametz (seeking out chametz) has evolved into a delightful way for parents and children to bond across the generations as we welcome Pesach. Passover holiday .

Since I was seven years old, I have been privileged to hunt for chametz. At first, this tradition began under the guidance of my grandfather Rav Tuvia Geffen in my hometown of Atlanta, Georgia, followed by doing so with my father Louis. In later times, I got to gather chametz alongside my own children both in America and Israel. There was even one memorable occasion where we were able to bring together four generations—my parents searched for chametz accompanied by their grandchildren and great-grandchildren during a visit to Atlanta from Israel for the festival.

Searching for pictures of bedikat hametz

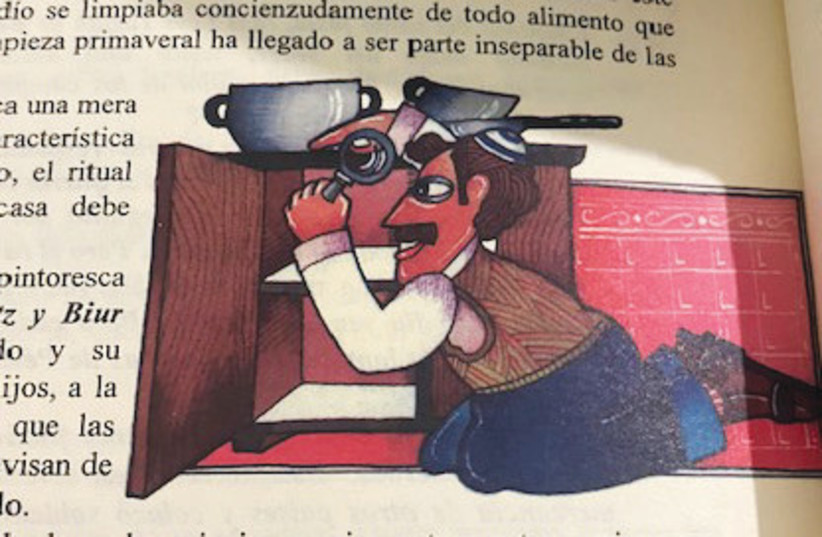

Moving forward: I possess a contemporary Haggadah from Mexico, printed in Spanish back in 1994 under the authorship of Rabbi Marcelo Ritner and Rabbi Felipe Goodman. This edition features an intriguing illustration depicting bedikat hametz. The scene shows a formally dressed, respectable man wearing a kippah atop his head along with a luxurious mustache gliding across the floor on his knees beside a kitchen cupboard following his examination. Various pots rest upon the cupboard, suggesting this area was also inspected. Clutched in his hand is a magnifying glass enabling him to scrutinize thoroughly for even traces of chametz remaining within the cupboard.

I've personally looked up images in specific Haggadot as well, such as the National Bank Haggadah printed in New York in 1920. This edition is a reproduction of an illustration from America’s first illustrated Haggadah, which was released in 1879.

The illustrations in this work were created by an artist named Senor. It depicts a boy carrying a torch alongside his father, both looking for chametz. This particular Haggadah holds considerable historical importance, having been republished numerous times up until the 1880s. Several editions can be found at the National Library, and I personally possess some as well.

I've also written my own work, the American Heritage Haggadah, published in Jerusalem. It features an illustration depicting the father guiding the search alongside his children. Though it’s no longer in print, this Haggadah can be found online. Indeed, the internet offers many representations of various Haggadot, featuring, naturally, illustrations of these texts. search for hametz .

An excellent resource is Ktiv, The International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts, an innovative project by the National Library of Israel aimed at providing worldwide centralized digital access to all extant Hebrew manuscripts. This platform stands as the most extensive online repository of Hebrew manuscripts globally, enabling me to view numerous images of Haggadahs preserved in various international libraries. Such works offer valuable insights into how Jewish life appeared "in those days."

Using Ktiv, I had access to stunning visuals from the 1478 Washington Haggadah, adorned by the distinguished medieval artist and writer Joel ben Simon (or Feibush Ashkenazi). This manuscript is currently preserved in the Library of Congress. At the top of the bedikat hametz page, you can see the term "Ohr" rendered in gold leaf.

The depiction at the base genuinely captures that era. It features two Jewish individuals clad in contemporary dress for their time, engaged deeply in some ritualistic activity. The person on the left stands beside what appears to be a cupboard, clutching a candle with one hand and holding a quill along with a basin in the other. Meanwhile, the individual on the right operates an old-fashioned water pump to ignite a flame used for disposing of leavened bread. Their clothing evokes memories from historical movies about the Middle Ages and the Renaissance era that I enjoyed as a child. Until now, I hadn’t considered how Jews might have been attired back then, yet isn’t this plausible? After all, they were integrated into societal norms and would therefore wear appropriate garments.

Another Haggadah I examined online comes from the Rosenthalia collection in Amsterdam. This distinctive version was crafted by Yaakov Yehuda Leib in 1741 in Hamburg. The individual conducting the ceremony in the depicted scene is adorned in attire that epitomizes a blend of Ashkenazi and Sephardic styles, showcasing a trendy look for that era.

At the National Library, there is a copy of the Prague Bohemian Haggadah dating back to 1526. Upon examining the page, it becomes evident that the figure depicted is prepared for the hunt for chametz. The illustration shows a bearded Jewish man clad in the clothing typical of that era, just before beginning the search for chametz within his dwelling. "Specifically for this task," he holds a candle in his right hand and, in his left, a feather to collect the crumbs along with a small bowl to hold them."

This illustration has been widely reproduced over the last five centuries, making it recognizable to Jews across the globe. Many individuals have had the privilege of viewing the real thing this year. Haggadah on exhibit at the National Library.

A different Haggadah housed at the National Library features an illustration related to the search for chametz that strikes me as having a comical aspect. Published in 1729 in Amsterdam by the renowned Proops print shop—which produced numerous Hebrew texts—this particular edition includes imagery where the patriarch wields a broom to sweep away the chametz onto a plate. Underneath the table crouches a small child carrying a candle. It appears that adhering strictly to the tradition involving candles remains essential during this process. The striking effect of the bold black-and-white woodcut used here really captures attention.

One of the key portrayals of Jewish existence during the 18th century comes from a publication by the French artist and engraver Bernard Picart, who was based in Amsterdam. His work, Rituals and Religious Customs of All Peoples of the World ("The ceremonies and religious customs of the various nations around the globe"), elegantly captures the adherence to Jewish traditions. A stunningly depicted moment shows housecleaning and the hunt for chametz: The mother, adorned in a graceful gown, guides the search at the table, brushing away residual hametz fragments as the men conduct their inspections of the floors and other spaces—holding candles and feathers, naturally.

One of the most esteemed modern Haggadot was created by the renowned artist Arthur Szyk. Notable scholar Irvin Ungar, who has studied Szyk’s art revival over the past 25 years, remarks: "The standout feature is the intergenerational aspect of performing bedikat hametz, where an elderly grandfather sits (possibly symbolizing ancestors from times gone by), while the father holds up a lit candle alongside his son. They seek out not just leavened bread but also hope for a more prosperous tomorrow."

Regardless of whether I sit or stand during the bedikat hametz this year, I am eagerly anticipating a brighter future ahead.

Chaplain David Geffen’s 'intense search for chametz' at Fort Sill

In 1991, Chaplain David Zalis came back after serving in the Gulf War in Iraq and Bahrain. MS Cunard Princess While aboard a vessel near the shores of Bahrain, where a Passover Seder was conducted, Zalis showed me an image of bedikat hametz taking place on the same ship. The excitement stemmed from recognizing some of the soldiers carrying out this ceremony, which reminded me fondly of my role as a chaplain during similar experiences.

Upon reporting for service in September 1965 as the Jewish chaplain stationed at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, I discovered that my predecessor had convinced the administration to provide the names of each incoming Jewish recruit. The recruits would spend eight weeks undergoing artillery training at Fort Sill prior to deployment to Vietnam. Armed with this list along with their specific tent or hut locations, I distributed copies of the fort’s chaplaincy newsletter directly to them every month. Sillouette .

A month prior to Passover in 1966, I resolved that each Jewish soldier stationed at Fort Sill—approximately 300 to 350 individuals—would be provided with a bedikat hametz kit containing a candle, a tiny box for holding the collected crumbs, and either a wooden spoon or a feather for gathering them. Acquiring the first three items was straightforward, but obtaining a feather posed more of a challenge.

In 1966, numerous Native Americans were still wearing traditional attire (indeed, Apache war chief Geronimo was interred at the Fort Sill Indian Agency Cemetery). Hence, I understood that there must have been a supply of feathers.

I approached several Jewish merchants in the town of Lawton, near Fort Sill, asking if they knew a Native American who dealt with feathers. They gave me some suggestions, and eventually, one led to something promising! I went to meet this dealer at the Apache reservation and expressed my desire to purchase 350 feathers. "That’s unfeasible," he responded. However, I didn’t give up. After negotiating, we agreed on 250 feathers, though I remained uncertain whether he could source such a quantity.

My chaplain’s aide obtained 250 candles from an assistant working with the Christian chaplains (we had both 25 Protestant and Catholic chaplains stationed at our location). To ensure soldiers receiving these items could perform crucial rituals correctly, we transcribed the prayers into their language. Then, we printed enough copies through stencil duplication. We agreed that matchboxes would serve as receptacles for leftover bits rather than lighting separate small fires outdoors, which might pose risks and likely violate rules. Instead, we directed participants to dispose of the boxes safely in garbage bins without starting any flames.

A couple of weeks ahead of Passover, we returned to the feather supplier. He mentioned he would include an additional 50 feathers at no cost, bringing the total up to 300. After paying him, we left with our acquisitions, all set for packing the bedikat hametz kits. My helper and I had previously arranged mailing packets, labeling each one with a soldier’s name and location. (Can you imagine getting such a package without also finding a solicitation inside?) Filling these envelopes, we then delivered them to the base postal service.

I didn’t inquire about the reactions of those who got the kit. However, we learned that a colonel—a singularly Jewish individual among the five officers with that rank stationed on the base—received the feather package, much to his astonishment. By mistake, one of the 25 non-Jewish chaplains based at Fort Sill also ended up receiving the kit. This chaplain contacted me stating that now he could observe Passover as well. To sum it up, the "bedikat hametz blitz" operation at Fort Sill was far more successful than anticipated.